Ophthalmoscopes: What Wikipedia Can’t Tell You

What is an ophthalmoscope?

An ophthalmoscope, the main player in the game of the ophthalmoscopy, is a device that combines a light and a built in set of mirrors and lenses, that allow doctors to examine the eye’s exterior and interior.

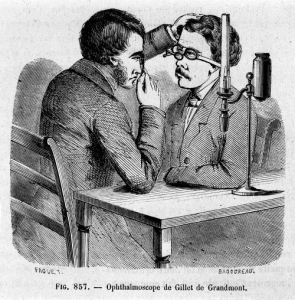

We can give a big thanks to Hermann von Helmholtz, who first got the ball rolling for the ophthalmoscope, but it has been over 150 years since the tool that was first known as the Augenspiegel, or Eye Mirror. Helmholtz, who was a physiology professor, used the instrument mostly to understand why sometimes the pupil of the eye appears black and at other times light. It was three years later, in 1854, that the tool changed its name to the Eye-Observer, and continued its evolution of changes, when Charles Babbage, an English mathematician and inventor in 1847, developed the instrument that most resembles the present day ophthalmoscope. According to Richard Keeler of The College of Optometrists, by 1913, “Edward Landolt reported that 200 models had been produced.” But at the core of each, according to Helmholtz, the three essential elements included 1) a source of illumination, 2) a method of reflecting the light into the eye, and 3) an optical means of correcting an unsharp image of the fundus. Although the tool continues to evolve, these three basic structures remain constant to this day. But what is the point of it all?

Your eyes are the window

Your eyes are the window to your soul… and also to your health! The eye is a network of complicated and sensitive vessels, tissues, systems, and more that work together to help you see. Take the matter into your own hands but don’t actually use your own hands. Instead, learn about the parts of the eye, the tools involved in checking them out (specifically the great ophthalmoscope), and the exam itself. Learning more about your body, health, and medical procedures applied to you is the first step in taking action.

Interior

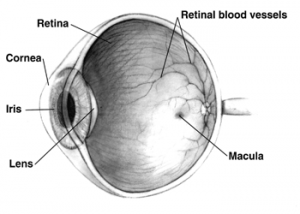

Just like a well designed living room area, the interior of an eye is organized, has a balanced system of reflecting lights, and a fine mixture of fragile and soft pieces. More specifically, the anatomy consists of:

- Iris: the colored part of the eye, responsible for controlling the pupil’s diameter, as well as the amount of light reaching the retina.

- Pupil: the opening in the center of the eye that accepts light into the lens, expanding and contracting.

- Lens: a transparent, biconvex structure that refracts light along with the cornea for the retina.

- Retina: a light-sensitive layer of tissue that, with the help of the cornea and lens, reads a visual image, and, through electrical impulses, sends the image to the brain.

- Macula: a small part in the retina that allows us to see fine details

- Optic nerve: links the retina to the visual cortex of the brain

- Vitreous: clear, jelly-like substance that is the center of the eye

Why get an ophthalmoscopy?

Although there are many parts of a complete eye examination, including vision and other tests, the ophthalmoscopy, commonly referred to as a detailed retinal exam, is a great place to start, and a part that should not be left out to assure that vision, general, and systemic health are up to speed. Your glossy peepers help you and your brain process visual information in front of you, but in the back of the eye, also known as the fundus, consisting of the retina, blood vessels, and optic disc, is where health and eye care professionals need to go to make sure you and your eyes are in tip top shape. To do so, a very routine examination will be performed. With it, it is possible to screen for eye diseases and conditions affecting blood vessels. Some of these conditions and problems include:

- diabetes

- glaucoma

- hypertension

- macular degeneration

- melanoma,

- cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis,

- damage to the optic nerve

- retinal tear or detachment

- retinopathy

- retinoschisis

- sickle cell retinopathy

- and other diseases

What happens during the exam?

There are three types of examinations that might be performed using ophthalmic tools. Think of your eyes as the center stage in a performance. Your doctor will dim or turn off the lights in the room, sit across from you, and examine your eye with an examination device that shines a light into your eye, like a spotlight on a dance solo, or musician.

Direct Examination

The aim with the direct scope is to get a general check of the nerve or macula. The device used is the size of a small flashlight with lenses that can magnify up to around fifteen times. This is the type of ophthalmoscope that is commonly used during a routine checkup. Your ophthalmologist will conduct where your eyes must move and before you know it, the exam will be over. Applause and flowers might follow, but probably just in your imagination.

Indirect Examination

In an indirect ophthalmoscopy, you will be asked to lie down or sit in a reclined position. A light attached to your doctor’s forehead, known as an indirect ophthalmoscope, will shine into your eyes, along with a small handheld lens. Today, these instruments may include a wide variety of features, which, according to Dr. Murat V. Kalayoglu of Ophthalmology Web, include “adjustable interpupillary distance, portable power packs, adjustable mirrors, dust sealed optics, and red-free and cobalt blue filters…video capture capabilities built in to some indirect ophthalmoscopes allow the patient to see his or her fundus on video and, in some instances, in real time.” (Helmholtz, Schepens, and Now: The Evolution of the Modern Binocular Indirect Ophthalmoscope, 2005). This device allows for a wider view of the eye’s interior, and allows a better view of the fundus. Again, you will be directed to look in different directions, and here, some slight pressure may be applied. Still, you should experience no pain. “The direct scope is good for a quick check of the nerve or macula,” claims Dr. Jennifer Lyerly, of Triangle Vision Optometry, “but if you want to see the full retina you are going to use a head mounted binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy.”

Slit-Lamp Examination

The last type of examination is known as a Slit-Lamp Examination, which gives your doctor the same view of your eye as an indirect examination, but with amplified magnification. The instrument, with a place for your chin and forehead to keep your head steady, will be placed in front of you, and you will assume the appropriate position. This tool used will be a non-contact lens or a Goldmann contact lens. While direct ophthalmoscopes are used commonly by students and physicians, eye care providers, i.e ophthalmologists and optometrists, will most likely only use the slit lamp biomicroscopy with a non-contact lens. A bright light will be turned on in front of your eye and your ophthalmologist will take a closer look, directing your eyes from side to side. Some slight pressure might be applied with a small, blunt probe, which might bring some discomfort, but most likely no pain, and any afterimages should go away after blinking several times.

Exam preparation

Prior to the actual exam, your doctor may use eye drops to dilate your pupils, making them larger and easier to look through. Prepare for someone to pick you up, as these drops may make your vision blurry and your eyes sensitive to light for the next few hours. Allow your eyes time to rest and recover under low lighting. Be sure to tell your doctor if you are taking any medications, have glaucoma or a family history of glaucoma, as eye drops may not be the right choice for you.

You know the drill

Relax your muscles, there is no actual drill! With no pain, there is no reason to avoid getting an eye exam and experiencing the technical and medical history of the ophthalmoscope first hand. With all the delicate parts of the eye and all of the visual intake the world has to offer, it is crucial to get your eyes checked and make sure they are healthy. According to medicinenet.com, “A recent survey showed that while nearly half (47%) of Americans worry more about going blind than losing their memory or their ability to walk or hear, almost 30% of those surveyed admitted to not getting their eyes checked.” People over the age of 40 should get their eyes checked at least every two years. Those over 60 should get their eyes checked at least every year. Nobody should put off a regular eye exam.

Appreciation:

For their time, medical expertise, input, and additions, special thanks to Dr. Jennifer Lyerly, Optometry Specialist, and Manqian Tu, Independent Optometrist and Healthcare Administration student at the George Washington University. Find Manqian’s contact information here: https://www.linkedin.com/in/manqian-amy-tu-4bb6b584

References:

Keeler, Richard. “A Brief History of the Ophthalmoscope.” The College of Optometrists. N.p., n.d. Web. <http://www.college-optometrists.org/en/college/museyeum/online_exhibitions/optical_instruments/ophthalmoscopes/>.

Kalayoglu, Murat V. “Helmholtz, Schepens, and Now: The Evolution of the Modern Binocular Indirect Ophthalmoscope.” OphthalmologyWeb. N.p., 16 Feb. 2005. Web. <http://www.ophthalmologyweb.com/Tech-Spotlights/26431-Helmholtz-Schepens-and-Now-The-Evolution-of-the-Modern-Binocular-Indirect-Ophthalmoscope/>.

“Ophthalmoscope.” MedicineNet. Ed. John P. Cuha. N.p., 6 Jan. 2015. Web. 12 Jan. 2016. <http://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=4645>.

One thought on “Ophthalmoscopes: What Wikipedia Can’t Tell You”

Comments are closed.