Wound Dressings 101: The Right Dressing for Each Type of Wound

We wouldn’t look so hot without our protective covering called skin. We really wouldn’t feel so great, either. One of the main functions of the skin is to protect the body against exposure to environmental toxins like bacteria. Among other duties, the skin keeps the blood vessels, nerves and organs under wraps while repelling outside water and containing internal water. So what happens when there is a puncture in the skin due either to surgery, injury or infection? When the skin is not able to perform and protect properly, enter: dressings.

We wouldn’t look so hot without our protective covering called skin. We really wouldn’t feel so great, either. One of the main functions of the skin is to protect the body against exposure to environmental toxins like bacteria. Among other duties, the skin keeps the blood vessels, nerves and organs under wraps while repelling outside water and containing internal water. So what happens when there is a puncture in the skin due either to surgery, injury or infection? When the skin is not able to perform and protect properly, enter: dressings.

Summary

Dressings are sterile pads or compresses that are meant to come in direct contact with a wound to protect it from further injury or infection and promote healing. Leaving wounds open to healing without dressings can lead to infections and severe scarring. Seems simple? Sort of. While the purpose of these aids is straightforward– to heal and protect the skin, dressings must be paired appropriately with the patient, circumstance, and wound type to actually promote healing. Choose the wrong dressing, and an infection might not heal and even lead to further medical issues. With over 3,000 types of dressings, it is important to know the functions and differences of each dressing style for appropriate application and optimal healing. It is also important to understand wound types to be able to create the perfect match so that skin can heal and once again work without the assistance of these temporary aids.

Purpose

Purpose

It is the job of the dressing to complete one or more of the following functions:

- Maintain a sterile, moist environment

- Absorb any outflow while preventing leakage to the dressing surface

- Provide protection from bacteria and outside intrusions

- Absorb wound odor

- Allow for secure placement, flexibility, and easy removal

- Be non-allergenic and suitable to use and change both for patients and medical staff

History

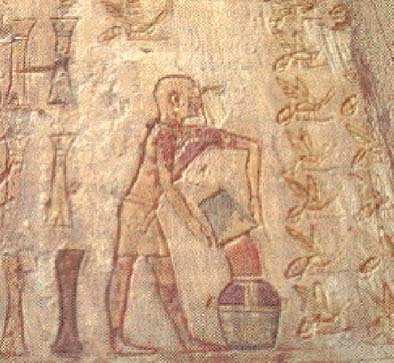

One. Wash the wound. Two. Make the plaster. Three. Bandage the wound. These practices that we know to be true now date back to 2200 BC. The basics are the same but a few substeps have changed along the way.

One. Wash the wound. Two. Make the plaster. Three. Bandage the wound. These practices that we know to be true now date back to 2200 BC. The basics are the same but a few substeps have changed along the way.

“Someone get me a beer,” you might say, if your body happened to inherit a wound. According to some of the first medical documentations, the Sumerians had a similar idea. However, instead of toasting to better health and downing the beverage, the urban Mesopotamian civilization used the substance in conjunction with turpentine, tamarisk, daisy, flour and milk for a plaster to be used directly on the skin. The combination of these ingredients provided protection against external environmental factors, absorbed exudate, promoted healing. Oil was another common ingredient in plasters, as it prevents sticking and creates a poor environment for bacterial growth.

Many regions had their own areas of expertise when it came to wound healing. In Egypt, common ailing ingredients included honey, grease and lint. The Greeks specialized in cleansing the wounds, bringing ingredients to the table such as boiled water, vinegar and wine. Later, they created the foundation of wound differentiation by creating a distinction between acute and chronic wounds and how to decipher the signs of inflammation.

It was the collaboration of these early efforts that brought us modern day medicine. The 20th century brought modern wound healing tools equipped with antibacterial properties and moisture keeping and/or absorbing elements such as alginates, foam, and more. While progress continues, current-day health care has accumulated generations worth of records and information to provide efficient and personalized care.

Assessment

Before picking a dressing, it is important to give the wound and the patient a careful evaluation. This means a current examination of the wound and the patient as well as the patient’s medical history. Look out for the:

- State of the injury

- Associated blood loss

- Contamination

- Structure damage

- Underlying nerve, vessel, and tendon damage

- Tissue damage or loss

- Tetanus history and status

- Presence of chronic illness or disability

Dressings and Minor Wounds

If a minor wound occurs on the body, there may not be a need to seek medical attention, but it is still important to treat the site to prevent infection and promote healing as soon as possible. If pain is not overwhelming and the wound is minor in size, follow these steps to try to aid the healing process at home:

- Wash and disinfect the site to remove any outside objects such as dirt or debris.

- Place pressure on the site and utilize elevation to control bleeding and swelling.

- Use a sterile dressing to wrap the wound, keeping it dry and clean for around five days.

- Acetaminophen can be used to assist with pain, but aspirin products should be avoided, as they cause or prolong bleeding.

- If the site begins to swell or bruise, applying ice may soothe the spot.

- If exposed to sunlight, place sunscreen over the area until the healing process is complete.

Dressings and Open Wounds

An open wound is classified by an internal or external break in body tissue. While some of these are minor injuries that can be treated at home, others call for more serious operations and healthcare guidance. With the variety of their functions, almost everyone has or will at some point have contact with dressings. Other more serious but common injuries that require wounds involve falls, contact with sharp objects, surgeries, and car accidents. In case of a medical emergency, call 911 immediately.

Open wound types

The type of wound and how it was received can indicate the type of dressing that will be required. Learn more about the different kinds of open wounds to find the most appropriate next step in healing:

Abrasion: An abrasion results from the skin experiencing friction to the point of scraping from contact with rough or hard surfaces. With abrasions, bleeding is typically limited. However, it is likely that the wound may be infected or may become infected. In either case, the wound needs to be cleaned.

Incision: Incisions are caused by the penetration of skin by sharp objects like knives, glass, or blades. When these open wounds occur, bleeding is often quick and heavy. In this case, damage can be done to tendons, ligaments and muscles.

Laceration: A laceration is a deep tear or cut in the skin or flesh often caused by knives or tools that leads to extensive bleeding.

Puncture: A puncture is a small hole created by an external pointy object. In some instances, punctures do not lead to too much bleeding. However, if penetrated deep enough, these wounds may lead to internal organ damage. To prevent infection, it is important to check in with a doctor and receive a tetanus booster shot, or make certain that you have received one within the suggested time frame.

Avulsion: This open wound involves the tearing of skin and tissue as a result of serious incidents often involving gunshots, explosions, and body-crushing accidents. In this case, bleeding is heavy and rapid.

When to seek help

If uncertain whether or not to seek medical attention, follow the suggested guidelines below if your wound is:

- Deeper than ½ inch

- Bleeding regardless of direct pressure being placed on contact

- Bleeding for longer than 20 minutes

- Bleeding as a result of an accident

Developing an infection is one of the major threats to having an open wound, and a reason that wounds should be taken care of immediately. Infections can lead to more severe issues and in some instances life threatening health scenarios, but what exactly would an infected wound look like? Here are some giveaways:

- Continuous bleeding

- Increase in redness, pain, or swelling

- Increase in drainage

- Pus that is thick green, yellow, or brown

- Pus that omits a foul odor

- A fever

- A sensitive lump in the armpit or groin area

- A wound that is not healing or getting worse

Treatment Options

Depending on the wound, there are a number of treatment options that a healthcare provider can offer. In some cases, the wound may be closed with skin glue, sutures or stitches. Puncture wounds may require tetanus booster shots. Medications and penicillin may be given if the patient is experiencing pain. If a doctor determines that an infection is present or may become present, antibiotics are likely to be distributed. In other instances, a variety of wound dressings are likely to be applied.

Wound Dressings

According to the wound type and severity, healthcare professionals can pick from a number of dressings to achieve quick and successful healing. Because these dressings are made with various features, it is important to know the characteristics of each type of dressing. One way to categorize dressings is passive, active, or interactive. Some dressings serve only to protect against outside harm and interference. These dressings are classified as passive, but a number of dressings do more to alter and maintain a certain environment that keeps contact with the wound. Active dressings, for example, work to create moisture around the wound to promote healing. Others may be considered interactive dressings.

Dry: Under this category is where you will find your standard bandage– the gauze pads that protect rolled gauze and tape, or simply the base gauze. This is a simple, inexpensive, and standard form of dressing, especially for dry wounds. If a wound omits a large amount of exudative, dry gauze may stick to the wound bed. To prevent this from happening with gauze, or when removing dressing that becomes stuck, it is possible to pour saline over the area for less friction and irritation upon removal. One of the major benefits of using dry dressings is protecting the wound against outside contamination, as well as preventing bacteria from entering and exiting the wound.

Wet-to-dry: Wounds that need to be debrided (removed of tissue that is dead, damaged, or infected) should be catered to with wet-to-dry dressings. To achieve such a dressing, it is possible to soak gauze or cotton in saline before placing it onto the wound. The drying process will dry the wound in its vicinity. While this can help in the cleaning and healing process, the extraction of tissue also has the potential to remove certain healthy tissues from the skin. This style of dressing utilizes inexpensive materials.

When to change

Let’s not forget the enemy that is infection. If a wound is open and left in close contact with too many fluids for long periods of time, an infection can occur. That is why it is crucial to keep an eye on dressings and keep track of their state and progression. When fluids soak through wounds, it is time to change the dressings. Ideally, dressings should be changed before they reach the point of soaking through the surface entirely. This is not only because of the risk of infection, but also because peeling gauze from the wounded area may prove to be more of a challenge. If newly-formed skin is broken, the wound may take longer to heal. If the wound does not excrete fluids, however, it is still important to change dressings after a shower, bath, or anytime they become wet, and the environment inside begins to alter. Of course, if something doesn’t feel quite right, it is time for a change. It is important to listen to how the body is feeling. Dressings should feel comfortable and secure. If that is not the case, change it and adjust.

How to change

When changing a wound dressing, the goal is to make the switch without causing the wound to open again. Depending on the dressing, the changing process may alter. Consult with the manufacturer or healthcare provider for specific instructions. For general guidelines, follow the rules below:

- Make certain that the materials are nearby. These most likely include: wound cleanser, your specific wound dressing, gauze, or bandage, disposable gloves, and antibiotic ointment, if it was prescribed.

- In the changing process, cleanliness is key. In order to prevent outside bacteria from creeping in, wash hands and put on disposable gloves when in the process of a wound dressing change.

- Carefully remove the old dressing. If the dressing has adhered to to skin, apply wound cleanser to help peel off the dressing. Throw away the old dressing in a plastic bag.

- Apply wound cleanser to the wound. If you were prescribed antibiotic ointment, apply that as well.

- Be aware of abnormalities including odor, excessive drainage, or a change in color. Keeping note of this throughout every stage of the process, even in the beginning, will help determine if an infection is present or arises at any point throughout the process. If this is the case, consult a healthcare professional.

- Apply a new dressing while maintaining the side that touches the wound as sterile as possible. Do not alter the wound’s environment by moistening the dressing or the wound.When the dressing begins to feel uncomfortable or is soaked through, repeat.

Complimentary Materials

While dressings have revolutionized the healing process, they can’t do it alone. These handy tools help get the job done:

Tape

Dressings would not be able to do their job if they kept falling off. While many dressings do come equipped with an adhesive to stay in tact, not all do. In any circumstance, it is important to have tape specific for wound dressings and wound dressing security. Tape can come in a few different forms including paper, plastic, or cloth. When being used with wound dressings, it is important to remove tape carefully. If adhesive sticks to the tissue or surrounding skin upon removal, further damage can be done. Leftover adhesive can be removed with remover wipes. Most patients experience a sensitivity to tape so remember to be gentle and do not overuse it. If a patient has a severe allergy to tape, it is possible to use rolled gauze as an alternative to secure with hypoallergenic tape. Another alternative is to secure dressings with cloth netting products.

Wound-Closure Materials

In determining how to close up a wound, there are several factors to consider including depth of injury, injury location, cost, availability, and allergies to any materials. A good place to start is to evaluate the type of wound to make sure it is ready to be closed. If you’ve got yourself an acute or uninfected wound, it might be time to close it up with sutures, staples, or synthetic glue. Sutures are stitches that close up a wound or surgical incision, and can be made from a number of materials including polyglycolic acid, polylactic acid, monocryl, polydioxanone, nylon, polyester, PVDF and polypropylene. The process of removing sutures depends on several factors including the depth of the wound and its location. In some instances, early removal is necessary in order to avoid scarring. To remove sutures, pull out a removal kit and use it with clean gloves on the hands. To remove staples, use a sterile staple remover. Glues usually slough off within seven to ten days following application.

Binders

A binder is a supportive bandage that wraps around the chest or abdomen and secures with ties or Velcro. Mostly used on larger incisions, these supportive aids are made from woven cotton, synthetic, or elastic materials. Binders can be attached and combined if a larger girth needs to be covered. It is important to be mindful of the pressure and tightness applied. If a binder has wrinkles, it could be an indication that the skin is experiencing too much pressure. Binders can be checked every four hours and re-wrapped every eight. They may also be replaced if exposed to bodily fluids.

Now that you are well versed in the general guidelines of wound dressings, let’s jump into the specifics. What are the most commonly used dressings, how do they operate, and how do you know when to pick what?

Hydrocolloid

Hydrocolloid dressings are wafer style dressings that utilize gel-forming agents on the inside with a water-resistant outside and provide a flexible hold. By using moisture and enzymes produced by the body, this dressing aims to create a moist environment for optimal healing for uninfected wounds, or those with low to moderate drainage. This dressing protects against outside bacteria and other invasive components. These dressings do not allow oxygen into the wound and have the potential to lead to anaerobic bacteria growth. Because of this, they are not recommended for already infected wounds, dry gangrene wounds, or dry ischemic wounds. Let’s break it down.

Hydrocolloid dressings are wafer style dressings that utilize gel-forming agents on the inside with a water-resistant outside and provide a flexible hold. By using moisture and enzymes produced by the body, this dressing aims to create a moist environment for optimal healing for uninfected wounds, or those with low to moderate drainage. This dressing protects against outside bacteria and other invasive components. These dressings do not allow oxygen into the wound and have the potential to lead to anaerobic bacteria growth. Because of this, they are not recommended for already infected wounds, dry gangrene wounds, or dry ischemic wounds. Let’s break it down.

How it works

Because they are occlusive and provide insulation, hydrocolloid dressings generate a moist healing environment. This allows the body’s enzymes to re-hydrate and moisten any necrotic tissue (made up of dead cells and debris). This process is known as autolytic debridement.

When to use

- When choosing a dressing, a hydrocolloid dressing is best used on:

- Non infected wounds with little drainage

- Necrotic or granular wounds

- Dry wounds

- Partial- or full-thickness wounds

- Newly healed wounds for extra protection

Advantages

- Easy application

- Self-adherent and secure hold

- Does not stick to or harm the wound

- May be used along with other protective or compressive products

- Creates protection against bacteria, contaminants, and environmental harms

- Depending on the wound, can be worn for several days

Disadvantages

- Depending on the dressing, progress assessment can be challenging if the dressing is opaque

- Not recommended for wounds that produce heavy exudate, infected wounds, or wounds with sinus tracts

- Patients with diabetes must take extra precaution when using hydrocolloid dressings. To ensure safety when using the dressings on foot ulcers, make certain a healthcare provider assesses the patient’s health, makes certain the wound is superficial with no signs of infection with low to moderate exudate, and there are no signs or symptoms of ischemia. In this case, dressings should be changed frequently.

- If the wound begins producing heavy exudate, the dressing could become dislodged.

- Residue may stick to the wound bed if not careful

- An odor may occur

- Periwound maceration may occur

- Hypergranulation may occur

Application

- First things first, wash hands and put on gloves

- If the patient has been using a dressing that is still in place, note the date that it was applied and remove the soiled dressing into a trash bag

- Remove gloves, wash hands, and put on new gloves

- Clean the wound with normal saline solution or cleanser, as prescribed

- Pat the surrounding tissue dry with gauze

- Remove gloves, wash hands, and put on new gloves

- Apply liquid barrier film or moisture barrier to periwound area

- If a wound is deep, consider applying wound filler

- Pick the appropriate size. The dressing should be larger than the wound by at least one inch

- Before contact of the dressing is made, hold the hydrocolloid between hands to promote adhesive ability

- Remove the paper backing on the dressing

- Place the dressing on the skin by applying it from the center of the wound outward and smooth in place

- Hold the dressing in place to confirm secure adhesion

- Tape can be applied around the edges for optimal security (optional)

- Throw away the remains

- Remove gloves and wash hands

Removal

- Place light pressure on the skin and cautiously begin lifting the edges until the adhesive is no longer stuck to the skin

- Peel away the dressing from the skin in the direction of hair growth

Changing

The frequency of dressing changes will vary from person to person but typically every three to seven days is most appropriate. Consider the amount of exudate and manufacturer guidelines. Hydrocolloid dressings are meant to remain on the wound for multiple days. If dressing changes are necessary more than the dressing allows, reevaluate the wound and the choice of dressing and check in with a healthcare provider.

For examples of hydrocolloid dressings, click here.

Hydrogel

Hydrogel wound dressings (also known as hydrated polymer) are made up of a base of nearly 90% water or glycerin. Inside hydrogel dressings, moisture and exchange of fluids is controlled in the wound site by absorbing minimal fluid while containing high levels of moisture by way of water or glycerin. This aids to soothe pain and increase tissue regeneration. These dressings are ideal for wounds with necrosis, infection, and some exudate. They should not be used on dry gangrene or dry ischemic wounds.

Hydrogel Dressings come in three forms:

- Amorphous hydrogel – hydrogel in gel form that is packed in tubes, packets, and bottles

- Impregnated hydrogel – hydrogel that is embedded onto a gauze pad, nonwoven sponge ropes and/or strips

- Sheet hydrogel – hydrogel that is supported by thin fiber mesh

How it works

The moist environment produced by hydrogel dressings promotes granulation, epithelialization, and autolytic debridement. The moisture as well as the high water content acts to cool and heal, giving the wound up to six hours of pain relief. While these dressings are not meant to stay up to seven days like hydrocolloid dressings, changing them is meant to be simple, as they do not adhere to the wound surface.

When to use

When choosing a dressing, hydrogel dressings are best used on:

- dry or slightly moist wounds

- painful wounds that need to be soothed

- partial- and full-thickness wounds

- wounds that reveal granulation tissue, eschar, or slough

- wounds classified as abrasions or minor burns

- wounds and skin suffering from radiation damage

Advantages

- Soothes and reduces pain

- Rehydrates the wound bed

- Promotes autolytic debridement

- With amorphous and impregnated hydrogel dressings, dead space can be filled

- Can work on infections

Disadvantages

- Due to less adhesion, hydrogel dressings may be challenging to secure on the body and in some cases may require a secondary dressing

- Could lead to periwound maceration

- Could dehydrate if not covered properly

Removal

- Wash hands and put on gloves.

- If a secondary wound dressing is in place, gently remove it.

- If an amorphous hydrogel dressing is in place, rinse away the remaining gel with a wound cleanser or normal saline.

- If a hydrogel impregnated gauze or hydrogel sheet is in place, lift the edges of the dressing and peel it away.

- In the case that the dressing has adhered to the wound surface, introduce wound cleanser or normal saline to gently remove the gauze or sheet.

- When removing the dressing, consider the residual exudate and reevaluate for further action.

- Discard the old dressing.

- Remove the gloves and wash hands.

Changing

As mentioned before, hydrogel dressings are not meant to last too long, but will vary from patient to patient. On average, hydrogel dressings should be changed anywhere from once a day to every four days, according to patient and manufacturer guidelines.

- Wash hands and put on gloves.

- Consider the date on the soiled dressing.

- Remove and dispose of the old dressing.

- Clean the wound with a wound cleanser or normal saline.

- Pat dry any surrounding tissue with gauze.

- Remove gloves, wash hands, and put on new gloves.

- Protect the skin from maceration by applying a liquid barrier film or moisture barrier ointment to the periwound area.

- Apply the new dressing and follow the below instructions for specific hydrogel dressing options.

- Dispose of the waste, remove gloves, and wash hands.

Amorphous hydrogel dressing

- Spread the product evenly over the wound bed with a sterile tongue blade or cotton-tipped applicator.

- The product should be spread to a thickness of 5 mm. Another option is for a sterile gauze pad to be combined with hydrogel and placed into the wound.

- Layer the hydrogel with a secondary wound dressing.

- Make certain the secondary wound dressing covers the entire wound bed.

- Dispose of the waste, remove gloves, and wash hands.

Gauze impregnated with hydrogel

- Lay the dressing on top of the wound or into the wound bed.

- Cover the initial dressing with a secondary dressing.

- Make certain the secondary wound dressing covers the entire wound bed.

Sheet hydrogel

- Trace the outline of the wound on top of the dressing with a marker.

- Cut the dressing accordingly using clean scissors.

- Apply the sheet on to the wound bed.

- Cover the sheet with a secondary dressing, which should cover the entire wound bed.

- Dispose of the waste, remove the gloves, and wash hands.

For more examples of hydrogel dressings, click here.

Alginate

Made of biodegradable material derived from brown seaweed, calcium, or sodium salts, alginate dressings have strong absorbency for exudate, and provide a moist environment. This helps to build hemostasis and prevents adhesion to the wound. Met with serum and wound exudate, the alginate dressings react to form a gel, which generates moisture while trapping bacteria, reducing the risk of infection or drainage. This dressing is ideal for ulcers, donor sites, tunneling wounds and bleeding wounds. A secondary dressing can be applied for double protection.

Fun fact: alginate dressings can absorb up to twenty times their own weight.

Fun fact: alginate dressings can absorb up to twenty times their own weight.

How it works

Is it magic, or is it alginate? Alginate dressings go on dry and gradually become larger and more gel-like as they absorb more fluids. Doing so aids in clearing out the wound while preventing it from drying out. By maintaining a moist environment, natural debridement is encouraged with the assistance of the body’s own enzymes. This process removes dead or damaged skin for optimal wound healing.

When to use

When choosing a dressing, alginate dressings are best used on:

- Sloughy wounds that produce exudate

- Shallow wounds with heavy exudate such as leg ulcers

- Cavity wounds packed with gauze and soaked in saline, hypochlorite, or proflavine, if the alginate fibre comes in ribbon or rope form

Advantages

- If well soaked in sodium chloride solution, alginate dressings can be easily removed without causing any pain.

- Flexible and comfortable, these dressings can be easily conformed, molded, and cut to accommodate a variety of wounds.

- The production of the gel and the resulting moist environment helps to prevent eschar formation and instead promotes healing.

- The environment created by alginate dressings allows for wound contraction, which can help reduce scarring.

Disadvantages

- Alginate dressings should not be used on wounds with little drainage.

- When properly functioning, the gel inside alginate dressings activates and encourages fast healing but in some instances, the gel does not form, which only increases the risk of irritation.

- Some allergies may occur. Make certain the patient is not allergic before usage.

- This dressing is not appropriate for wounds with little drainage. Due to their strong absorbency, alginate dressings could dry out such wounds.

Application

- Clean the wound area with normal saline solution.

- Pat the surrounding tissue and skin dry.

- Place the alginate dressing over the wound.

- To hold it in place, put a secondary dressing on top.

Changing

Due to a variation of wounds and amounts of exudate, check the dressing frequently and be sure to change the dressing every one to three days, or when moisture or fluid begins to seep out from the edges. If removal appears difficult, add saline to dampen the adhesion.

For more examples of alginate dressings, click here.

Collagen

Collagen dressings come in a variety of forms from gel to pads to powders and more. The power of collagen comes from its ability to promote tissue growth for minor to extensive wounds.

How does it work?

Dressings infused with fibroblasts and keratinocytes (cells that deliver certain ailing fibers) deliver flexible and useful properties that work to rebuild the wound bed back to health. The reason collagen is so useful in the body is because it is the major protein found in the extracellular matrix.

Advantages

- Collagen has the ability to heal a number of wounds from bed sores to minor burns to foot ulcers and more.This dressing is comfortable and flexible.

- The non-adherent qualities allow the dressing to feel loose and prevent sticking or irritation to the injured area.

- Collagen reduces the potential for wound infection by preventing bacterial build up with antimicrobial agents.

- Collagen dressings can last on contact for up to seven days, allowing for less frequent dressing changes.

- Collagen can come in gel form, paste, powder, or pad. The sizes of this dressing vary as well.

Disadvantages

- Wounds that cannot be treated with collagen dressings include third-degree burns, wounds that have developed eschars or burnt dead tissue.

- This dressing is not compatible for patients who have an allergy to cattle, bird or swine products.

- The lack of adhesion requires a secondary or cover dressing for security.

| Dressing Type | When to Use |

|---|---|

| Hydrocolloid |

|

| Hydrogel |

|

| Alginate |

|

| Collagen |

|

Other forms

Composites

Made up of multiple layers, the composite or combination dressings are embedded with a non-adherent as the base layer for protection followed by a middle layer that absorbs moisture away from the wound bed while still maintaining a moist wound environment. A protective outer layer acts as a barrier against outside interferences.

Foam

Sealed by semipermeable polyurethane, foam dressings feature open cells that are made for holding fluids and keeping wounds moist. These dressings are useful for wounds that are in early-stage pressure ulcers, as they are gentle and limit rubbing. Many of these foam dressings are self-adherent.

Transparent Film

Transparent film is not recommended for infected wounds, but is meant to keep out excess water and contaminants. Made of hypoallergenic and waterproof latex-free adhesive, this dressing provides breathable, sterile protection for the reduction of anaerobic bacterial growth. Because these dressings allow for longer wear time, there is less need for waste of materials such as gauze and tape. Less time is needed from nurses to prepare and change the materials, and less use of other prep materials such as gloves. Best of all, patient application is simple, secure, and efficient.

Chemical-impregnated

Some dressings are embedded with chemicals aimed to heal specific wound types. Some of these chemicals include betadine, silver, petroleum, collagen, and antibiotics. If these dressings come in sheet form, they may need secondary dressings for further support. Be sure to check with healthcare providers to ensure that the dressing is the right fit and to prevent allergic reactions in contact with the chemicals.

Port

Port dressings are made specifically for implanted venous ports and Huber needles. These dressings also provide a transparent seal with antimicrobial protection for the comfort of doctors and patients. The gel pad protects the Huber needle at the point of insertion for single or dual ports. This dressing presents versatility, as one size fits all by accommodating a variety of needle insertion options.

Due to the healing process which is constantly adjusting, most patients need two or more types of dressings at different stages. It is therefore crucial to reassess the state of the wound.

Body and mind healing

No matter the wound type or wound dressing used to aid in the healing process, it is not uncommon for the body and mind to experience large amounts of stress throughout this time. If the patient obtained wounds through a particularly traumatic accident, there is a possibility of experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder, which can lead to social, psychological, and physical problems in the recovery process and beyond. In times of recovery, it is important for patients to learn how to maintain a healthy outlook for the body to heal properly and efficiently.

Forward

While we are further in understanding wound and wound care than ever before, the aim for progress is not over. Join the discussion and consider how the medical community can help improve wound care. Click here for Dr. Tomas Serena’s thoughts and more.

Article Resources:

- Roddick, Julie. Higuera, Valencia (2015, September 16). Open Wound. Retrieved from http://www.healthline.com/health/open-wound#Types2

- Swezey, Laurie. (2010, September 21). Interactive Wound Dressings. Retrieved from http://woundeducators.com/interactive-wound-dressings/

- Morgan, Nancy. What you need to know about hydrogel dressings. Retrieved from http://woundcareadvisor.com/apple-bites-vol2-no6/

- Advanced Tissue (2014, December 5). Your Guide to Hydrocolloid Dressings. Retrieved from http://www.advancedtissue.com/guide-hydrocolloid-dressings/

2 thoughts on “Wound Dressings 101: The Right Dressing for Each Type of Wound”

Comments are closed.