Blood Pressure Tech 101: Everything You Need to Know

Everything you need to know about monitoring blood pressure

Blood pressure, or BP, is one of the vital signs that let medical professionals know how healthy an individual is. This is why it’s so crucial that it is measured accurately. BP is the pressure created by the circulation of blood on the walls of blood vessels and the term is usually taken to mean the arterial pressure in systemic circulation, unless otherwise qualified.

In this guide, we go in depth into the issues surrounding blood pressure and discuss the various available measurement devices, BP cuffs, and technology to help you make an informed choice when it comes to choosing the right device for your patients.

A brief history of the study of blood pressure

Blood circulation has been a source of fascination for millennia. The ancient Chinese are reputed to be the first to have noticed that blood traveled through a network of veins and arteries in the body and came up with a number of theories around how the circulatory system might work. However, there is evidence to suggest that scientists in India also identified the circulatory system and its connection to heartbeats.

In 1628, William Harvey, a doctor in London, UK, deepened the medical community’s understanding of the circulatory system with his seminal tome Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (On the Movement of the Heart and Blood in Animals), a text that is still held in high regard.

After the connection between pulse and heart rate had been determined, it was not long before a method was devised to measure blood pressure and volume. In 1733, an English clergyman, Reverend Stephen Hales, was the first to record a horse’s blood pressure. He inserted a glass tube into an artery and noted how the pressure increased as blood was pushed up it.

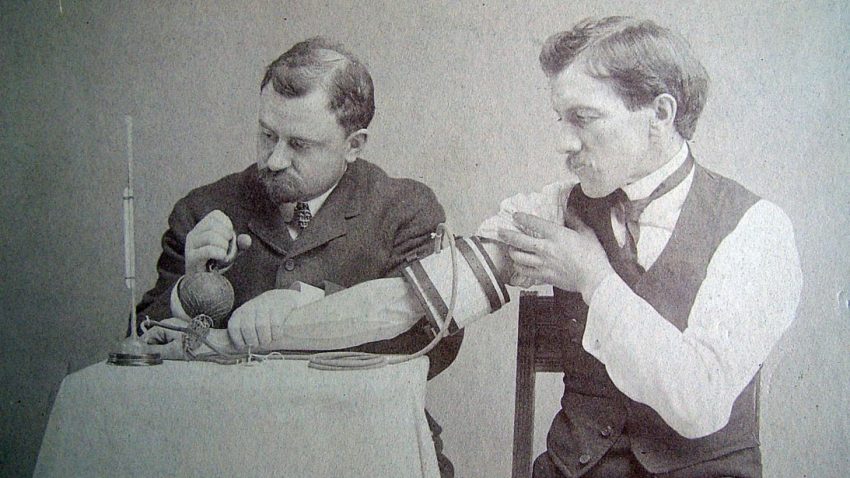

Samuel Siegfried Karl Ritter von Basch invented the first sphygmomanometer in 1881

It wasn’t until 1881 that Austrian Samuel Siegfried Karl Ritter von Basch invented the first sphygmomanometer to measure blood pressure. His primitive device was comprised of a rubber bulb that held water to limit the artery’s blood flow. This was then attached to a mercury-filled column that would convert the pressure necessary to stop the flow into millimeters of mercury, a measurement we still use today. Over time, others honed the design and in 1896 Italian Scipione Riva-Rocci introduced the first cuff-based device that could be wrapped around the upper-arm for even distribution of pressure. His basic design formed the template of modern devices.

The final piece in the puzzle was discovered in 1905 by the Russian surgeon Dr Nikolai Korotkoff, who observed the difference between systolic and diastolic pressure. It is these two measurements that are used in modern blood pressure measurements.

How do you measure blood pressure?

Taking someone’s blood pressure is a quick, simple, and painless procedure that can be carried out at a doctor’s office, at a pharmacy or even in a patient’s own home. First, a blood pressure cuff is wrapped around the patient’s arm. This cuff has a gauge on it to measure BP. The medical professional then inflates the cuff, which will squeeze the arm, but not cause any discomfort. Once the cuff is fully inflated, the doctor or nurse will slowly deflate it while listening to the patient’s pulse with a stethoscope and observing the gauge to obtain the relevant measurements.

Taking someone’s blood pressure is a quick, simple, and painless procedure that can be carried out at a doctor’s office, at a pharmacy or even in a patient’s own home. First, a blood pressure cuff is wrapped around the patient’s arm. This cuff has a gauge on it to measure BP. The medical professional then inflates the cuff, which will squeeze the arm, but not cause any discomfort. Once the cuff is fully inflated, the doctor or nurse will slowly deflate it while listening to the patient’s pulse with a stethoscope and observing the gauge to obtain the relevant measurements.

Alternatively, a patient may choose to get their blood pressure measured at one of the machines that can be found in many pharmacies or even obtain a home monitoring device so they can take regular readings as required.

Why is blood pressure so important?

BP is generally expressed as the systolic (highest during one heart beat) pressure over diastolic (lowest between two heart beats), measured in millimeters of mercury (mmHg) over the surrounding atmospheric pressure. Mercury is still the standard unit of measurement for pressure in medicine following its use in early sphygmomanometers.

A healthy, resting blood pressure in an adult is around 120 mmHg systolic and 80 mmHg diastolic, or 120/80 mmHg. However, this can vary depending on circumstances, emotional condition, activity and overall health.

As long as a patient’s blood pressure is within normal ranges, there should be no cause for concern. However, if an individual’s blood pressure regularly measures outside of normal ranges, this could be a sign of a serious underlying issue. The higher the blood pressure, the greater the chances of developing health problems.

The five blood pressure ranges

There is only one way to be certain if a patient is suffering from high blood pressure or hypertension: take a blood pressure reading. Before taking any action, any concerns about BP readings should always be confirmed with a medical professional. They will also be able to advise if a patient is suffering from an abnormally low reading, taking into account any underlying health concerns such as diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease.

The American Heart Association identifies five different ranges or stages of blood pressure. Anything under 120/80 mmHg is considered to be normal, while a result between 120-139/80-89 mmHg is classed as ‘prehypertension’ or early stage high blood pressure. A patient whose blood pressure falls within this range is considered to be at risk of developing high blood pressure unless preventative action is taken.

Blood pressure ranges

A patient is classed as having hypertension stage 1 when their BP is regularly measuring within 140-159/90-99 mmHg. At this stage, medical professionals are most likely to recommend lifestyle changes, although this may also be supplemented with blood pressure medication. Hypertension stage 2 comes when a patient’s BP is regularly over 160/100 mmHg. If BP is this high, it is highly likely the blood pressure medication will be considered necessary in conjunction with lifestyle changes.

A patient will suffer a hypertensive crisis if their BP is over 180/110 mmHg. If a patient’s BP is this high but they are not experiencing any other symptoms, e.g. chest or back pain, shortness of breath, problems speaking, wait for five minutes and take another reading. If it still measures at that level (or higher) and the patient is not in a medical facility, call 911 immediately for emergency care.

There are two types of hypertensive crisis: hypertensive urgency; and hypertensive emergency.

Hypertensive urgency is the term for when BP goes up to 180/100 mmHg or higher but without causing harm to any organs. In this instance, blood pressure medication should be enough to resolve the problem. Hypertensive emergency is the term for blood pressure that is so high that it can cause organ damage and requires treatment in an intensive care unit. Left untreated, a hypertensive emergency can cause major health issues, including stroke, heart attack, eclampsia or kidney damage.

The risks associated with persistently high blood pressure

When a patient suffers from hypertension, damage is initially caused to the arteries and heart. With increased BP, the heart and blood vessels have to work harder and gradually the force of elevated blood pressure harms the interior of the arteries. As this continues, atherosclerosis starts to develop as LDL cholesterol causes plaque to build up along these tiny tears in the artery walls.

As this process continues, the continuing damage to the arteries makes the path through the arteries more and more narrow, causing blood pressure to increase even further, perpetuating the cycle and increasing the risk of more serious conditions.

What makes hypertension so serious is that all this harm can be symptomless, so although a patient feels perfectly healthy, their blood pressure is causing severe damage to their body. The most effective way of avoiding this downward spiral is to make sure that patients are aware of their BP readings and are advised to make any appropriate changes necessary to manage their hypertension or avoid developing it in the first place.

Recent research suggests that the chances of someone dying from ischemic heart disease or stroke doubles with every increase of 20 mmHg systolic or 10 mmHg diastolic in patients aged 40-89. Approximately 1 in 3 adult Americans have high blood pressure, but it is estimated that only half of those affected are treating it. This makes it all the more important to diagnose high blood pressure early so that it can be treated before it becomes life threatening.

The risks associated with low blood pressure

As a general rule, the lower your blood pressure, the better. There is no specific number that is classified as too low; low blood pressure is only a problem if there are other symptoms presenting. These include:

- Dizziness or feeling faint

- Nausea

- Syncope or fainting

- Feeling dehydrated or unusually thirsty (which may be a cause rather than a symptom of low BP)

- Problems concentrating

- Blurred vision

- Skin feeling cold or clammy or looking pale

- Feeling fatigued

- Depression

If someone is experiencing any of these symptoms, it would be worthwhile diarizing when these occurred, along with a note of what activities they were engaged in at the time so that their healthcare professional can determine if there are any underlying problems that need to be dealt with.

There are a number of reasons why someone may experience low blood pressure, many of which are no cause for concern. For example, it is normal for blood pressure to drop during the first 24 weeks of pregnancy; this would not be anything to worry about.

Other causes of low blood pressure include:

- Long term bed rest

- Loss of blood, e.g. following major trauma or dehydration

- Certain medications, such as beta blockers, tricyclic antidepressants and narcotics, as well as some over-the-counter and prescription drugs when taken in conjunction with drugs used to treat high blood pressure

- Heart issues, e.g. bradycardia (low heart rate) or heart failure

- Endocrine issues, e.g. hypothyroidism or diabetes

- Septic shock

- Anaphylactic shock

- Neurally mediated hypotension, which usually affects young people, causing BP to fall after standing for a long time

- Malnutrition, e.g. lack of vitamin B-12 or folic acid

The importance of monitoring BP in critical care

Blood pressure is one of the eight vital signs of patient monitoring, the other seven being temperature, pulse, respiratory rate, SpO2, pain, level of consciousness and urine output. In a critical care situation, this makes it crucial that accurate BP readings are obtained. Studies have shown that a sudden drop in BP can indicate a pending cardiac arrest, so although cardiac issues aren’t certain, should a patient experience a dip in BP, they should be given a more thorough examination to make sure that they aren’t in any immediate danger.

However, just a small inaccuracy in a BP reading can have devastating consequences. If a BP reading consistently underestimates diastolic pressure by just 5 mmHg, hypertension could go undiagnosed, leaving the patient vulnerable. Yet blood pressure is one of the most frequently misread signs, due to an overreliance on automated devices either because of a lack of training, confidence or time.

In some instances, it has become common practice to redo a BP reading, not to confirm the initial figures, but to adjust them to more normal bounds. This observer bias, where the medical professional manipulates the situation until they get the result they want, could potentially be viewed as professional misconduct and cause serious legal issues, not just for the individual concerned but also for their healthcare facility. It is vital that all staff are aware that BP measurements should be a true and accurate reflection of a patient’s condition at any given moment and if an automated device is giving varying results, blood pressure should be checked manually with a sphygmomanometer.

One alternative to using an automated device in critical care is to measure arterial BP by inserting a cannula into the radial, brachial, femoral or dorsalis paedis artery and then connecting this to a calibrated transducer. This will convert the pressure into an electrical signal, which is easily monitored, and has the added advantage that it also allows for blood samples to be taken as needed. This can only be carried out by a trained clinician and is exclusively for use in hospitals, most commonly in the intensive care unit or the operational theater.

However, it is worth bearing in mind that arterial blood pressure cannot be relied upon as a gauge of cardiac output, since this is heavily influenced by systemic vascular resistance or SVR. Critically ill patients tend to have a highly variable SVR, which could be low if they are in septic shock or high if they are in cardiogenic shock, so if arterial BP is being monitored, this should be in conjunction with other observations.

If a large drop in mean arterial pressure (MAP) is registered, this frequently means that vital tissues are not receiving an adequate blood flow, which may result in brain or kidney failure. This makes arterial BP monitoring a very useful approach in monitoring critically ill patients, particularly essential if inotropic and/or vasopressor drugs or anaesthesia are being utilized. Be aware that there can be a number of complications caused by arterial catheters, including thrombosis, embolism and infection, and staff should be aware of these potential issues so they can be on the alert for warning signs.

Sphygmomanometers

Blood pressure is usually measured using a sphygmomanometer, sometimes known as a blood pressure meter, monitor or gauge. A sphygmomanometer is comprised of a cuff, a method of inflating the cuff and a mercury or mechanical manometer that measures the blood pressure on the artery as it is collapsed then released. Manual sphygmomanometers are used alongside a stethoscope to note the point at which blood flow begins and when it is fully unimpeded, while automatic sphygmomanometers are able to measure this without the need for extra equipment.

Blood pressure is usually measured using a sphygmomanometer, sometimes known as a blood pressure meter, monitor or gauge. A sphygmomanometer is comprised of a cuff, a method of inflating the cuff and a mercury or mechanical manometer that measures the blood pressure on the artery as it is collapsed then released. Manual sphygmomanometers are used alongside a stethoscope to note the point at which blood flow begins and when it is fully unimpeded, while automatic sphygmomanometers are able to measure this without the need for extra equipment.

There are three different types of sphygmomanometers: mercury and aneroid sphygmomanometers (both manual) and digital sphygmomanometers. Mercury sphygmomanometers are the most accurate, showing BP by changing the height of a column of mercury, which means that it never needs to be recalibrated. Since they are so precise, they are frequently used in drug trials or when a patient is considered to be high-risk.

Aneroid sphygmomanometers are mechanical devices with a dial. Unlike mercury sphygmomanometers, they do need recalibration, although they are considered to be safer, if less accurate. The results can be skewed if the device is jarred, although if the sphygmomanometer is mounted on a wall or stand, this can be avoided.

Digital sphygmomanometers work in a different fashion to manual types, using oscillometric measurements and electronic calculations to determine BP. Some also measure arterial stiffness and/or irregular heartbeats. These electronic devices can inflate either manually or automatic and are easy to use and do not require quiet surroundings to hear the results. The cuff may be placed around the upper arm, wrist or finger, making them more convenient to use and some patients may find them more comfortable. However, they aren’t as accurate as mercury sphygmomanometers and may require calibration. They are not suitable for use with patients who suffer from any of a range of conditions, including arrhythmia and preeclampsia.

Obtaining accurate BP measurements

We’ve covered some of the reasons why you need to get as accurate a BP reading as possible, but how exactly do you go about doing that?

First of all, you need to make sure you have the right equipment on hand. You’ll need a stethoscope, the right size blood pressure cuff.

Ensure your patient is as relaxed as possible. So-called ‘white coat syndrome’ can result in a falsely elevated reading if a patient is stressed about visiting their medical professional, so take a few minutes to put them at ease.

Once you’re ready to take a reading, have your patient sit up straight with their feet firmly flat on the ground and their upper arm relaxed, level with their heart. If the patient is wearing long sleeves, get them out of the way of the cuff, either by removing them or pushing them up to the upper arm. Take care that this doesn’t affect blood flow.

It is imperative that you select the right BP cuff size. Many inaccurate readings are caused by using the wrong cuff size. Check that you have the correct size by wrapping the cuff around the patient’s arm and ensuring that the index line shows that their arm is within the range area for the cuff. If not, use a smaller or larger cuff, as appropriate.

Locate the brachial artery and wrap the cuff around the arm so that the artery marker is indicating the brachial artery. Now palpate the arm at the crease until you find the location of the strongest pulse sounds and put the bell of the stethoscope over the brachial artery at this point.

Pump the cuff bulb to inflate the cuff while you listen to the pulse. Neither you nor your patient should talk during this part of the process. When you cannot hear anything through the stethoscope, this is an indication that the cuff has stopped the blood flow. If you know the patient’s usual BP reading, the gauge should be at around 30-40 mmHg over this figure. If you don’t know their normal BP, inflate the cuff to 160-180 mmHg, although you can go higher if you hear pulse sounds immediately.

Now you can deflate the BP cuff. The AHA advise that this should be done slowly, at a rate of about 2-3 mmHg per second. If you deflate the cuff any faster, you are likely to get a false reading. As blood flows through the artery again, you’ll start to hear rhythmic sounds, which may sound a little like tapping. This is the systolic reading.

Carry on listening as the cuff continues to deflate. The noises will fade away and when you can no longer hear anything through the stethoscope, note the reading on the gauge again. This is the diastolic reading.

To ensure you have an accurate reading, the AHA advises taking the blood pressure from both arms and then average the two results. It is best to wait five minutes between readings to give the patient’s body a chance to normalize. It is normal for blood pressure to be higher in the morning and gradually go lower throughout the day, so be aware of minor individual variances. If, however, you are concerned about the reading or you suspect hypertension caused by white coat syndrome, you may decide to carry out a 24 hour BP study to gain a more accurate picture of the patient’s general blood pressure.

Controlling hypertension

A clinical trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health has shown that actively managing high BP has a significant impact on the risk of developing cardiovascular disease and reduces the risk of death in adults aged 50 and over suffering from hypertension. The trial used medication to achieve a target systolic pressure of 120 mmHg saw the number of cardiovascular events and strokes decrease by almost a third, while deaths went down by almost a quarter compared to those with a target systolic pressure of 140 mmHg, showing just how important low blood pressure is to staying healthy.

If a patient has been diagnosed with prehypertension or hypertension, there are a number of approaches that can be taken to get BP back within normal ranges. Eating a heart-healthy diet and appropriate exercise are simple ways that can have a powerful impact on high BP, and losing weight can also be of massive benefit. For example, cutting back on salt can reduce systolic BP by 2-8 mmHg, while a 30-minute daily walk can further take that number down by 4-9 mmHg.

If diet and exercise alone aren’t enough, doctors frequently prescribe a thiazide diuretic to combat hypertension. These may also be called ‘water pills.’ However, if these are not appropriate, there are alternative medications available.

Home BP monitoring

For patients with prehypertension or hypertension, it may be worth investing in an at-home BP monitor so they can obtain a clear picture of their BP over time. This should be done following discussion with their medical professional to see if this is the right approach, as well as assist them in determining the right cuff size to purchase. At-home monitoring is recommended by the American Heart Association for those who are being treated for hypertension to measure the effectiveness of treatment.

The types of patients who may benefit from at-home monitoring include:

- Patients beginning treatment for hypertension to see how they react to medication

- Patients with certain conditions that necessitate close monitoring, e.g. coronary heart disease or kidney disease

- Pregnant women at risk of preeclampsia or pregnancy-induced hypertension, both of which can become very serious very quickly

- Patients who suffer from white coat syndrome and need to confirm if they genuinely have hypertension

- Patients who have had high readings from their doctor and would like to check if they have hypertension

However, if a patient suffers from any form of arrhythmia, they may not benefit from home monitoring, which could give misleading results.

Home monitors are available with either wrist and arm cuffs. Arm cuff monitors usually come with risk category indicators, giving warnings if there are high readings. Some digital monitors also allow for more than one person in the household to use the device, storing individual results separately. If a patient chooses an arm cuff monitor, it is vital that they choose one with the correct size cuff or the results will be invalid.

Home monitors are available with either wrist and arm cuffs. Arm cuff monitors usually come with risk category indicators, giving warnings if there are high readings. Some digital monitors also allow for more than one person in the household to use the device, storing individual results separately. If a patient chooses an arm cuff monitor, it is vital that they choose one with the correct size cuff or the results will be invalid.

Wrist monitors are more compact and easily carried around. Fully automatic, they can be less accurate than arm monitors, so it is important that the cuff is placed at heart level for the most precise result.

There can be problems with home monitoring. Patients don’t always follow medical advice, so may not monitor themselves appropriately. Depending on the type of monitor they choose, it may not be giving accurate information and patients may not always follow through with providing their doctor their results. This is why it is worth it for patients to invest in a home blood pressure monitor that takes accurate readings and automatically sends them to their clinician, relieving the patient of the responsibility of keeping their doctor informed. This has the added advantage of allowing the physician to see whether a patient is listening to their recommendations without needing to follow up for information.

Disposable vs. reusable blood pressure cuffs

Medical professionals can choose between using disposable or reusable cuffs when measuring blood pressure. Studies have shown that patients can be exposed to Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs) in healthcare facilities from reusable medical equipment, such as BP cuffs. With over 70% of bacterial infections resistant to antibiotics, prevention is the best way to ensure patients don’t have to suffer unnecessarily.

The average cost of treatment for HAIs is $23,226 per patient, which is a major financial burden, totaling an estimated $45 billion p.a. in the United States. When CMS stated in October 2008 that it would not cover the cost of treating numerous HAIs acquired during hospital stays, it put the onus on healthcare facilities to take all preventative measures possible to avoid patients contracting an HAI, especially since many private insurance companies have also said that they are considering similar policies.

In addition, the Department of Health and Human Services is being pressured to put in place regulations forcing hospitals to make public the rate of HAIs among their patients. 27 states already have such laws in place. These are Alabama, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington and West Virginia. These regulations are meant to ensure that hospitals do everything they can to reduce HAI risks and provide a safe environment for their patients. It also allows consumers and employers to make an informed decision about their healthcare facility.

Reusable BP cuffs are a major source of bacterial contamination and contribute to the spread of HAIs. It cannot be assumed that cleaning with disinfectants is enough to make a reusable BP cuff safe for future patients. Studies have shown that disinfectants are not effective in removing all microbial life from cuffs, especially Clostridium Difficile (C. diff), which is resistant to most disinfectants.

Over 2 million Americans contract an HAI every year necessitating on average an extra 8 days in hospital and requiring extra healthcare resources. They are also at an increased risk of readmission and death. 99,000 Americans die of HAIs p.a. and all healthcare facilities should be working to reduce this number.

The highest contamination rates are in Intensive Care Units and from nurses’ trolleys, but every department should be aware of this major health risk and opt for disposable cuffs where possible.

Saving money by standardizing BP cuffs

Many healthcare facilities have been able to improve patient care while cutting back on costs by standardizing their BP cuffs. There are a number of reasons why a facility might want to consider standardizing:

- It improves patient safety by enabling single-patient- use workflow, reducing the risk of cross contamination

- Standardization makes it easier for healthcare professionals to find and use the right sized cuff

- Many options are available that enable facilities to reduce their environmental impact by over 60% according to an analysis carried out by the Center of Sustainable Production at Rochester Institute of Technology

- Standardization offers greater reliability and improves consistency throughout the facility, benefiting both staff and patients

- It streamlines the number of suppliers a facility has to deal with and simplifies inventory

- Most importantly for the bottom line, standardization reduces SKUs and excess inventory costs, which may save healthcare facilities as much as $140k. (Based on results following standardization at Grady Health System, Atlanta, GA.)

One popular choice when deciding to standardize are the Welch Allyn patented FlexiPort® blood pressure cuffs, available in both reusable and disposable versions.

Welch Allen FlexiPort® Cuffs

One of the advantages of the FlexiPort® system is that every cuff becomes either a one- or two-tube cuff, making it very simple to switch cuffs between patients. The cuffs are color coded to make it easy to find the right cuff size at a glance, reducing staff confusion and obtaining more accurate readings. Tubing can be attached and detached single-handedly, saving time, while the rotatable port minimizes stress to the cuff tubing and port, making the cuff last longer while improving patient comfort.

The cuffs are latex-free to minimize the chances of an allergic reaction, while the folded edge cuts down on the risk of cuts and scrapes, which helps to protect the patient from HAIs. They meet all the latest aaMI and aHa clinical guidelines for proper fit and are available in almost every type, size and configuration.

When a facility standardizes, it makes it much easier for everyone to do their job effectively and efficiently, improving patient care and bringing down costs.

How to choose the right reusable cuff

Many healthcare facilities find that a combination of reusable and disposable BP cuffs is the best solution for their needs. There are a number of different types of reusable cuff available. These include:

- Single patient use. These are cuffs designed to be reused with an individual patient who will be staying longer-term.

- Limited reuse. These are designed to be easy to clean and withstand multiple inflations while remaining economical for single patient use.

- Hospital reusable. These are the most affordable types of cuffs.

- General care reusable. These are designed to be used multiple times and withstand repeated disinfection and cleaning.

There are a wide range of cuff sizes available, including neonate, pediatric and adult, with options for both forearm and thigh. Given how important fit is in determining an accurate reading, healthcare facilities should always have a wide range of sizes in stock to deal with all possible scenarios.

The future of BP monitoring

Blood pressure will always be a very important metric to determine patient health. Hypertension is a serious issue and can be life-threatening, yet is known as the ‘silent killer’ because it can be symptomless until it’s too late. This is why it is so important for patients and their physicians to be aware of their blood pressure so that preventative treatments can be put into place to undo the damage caused by high blood pressure. It is never too late to make simple lifestyle changes that can combat hypertension.

Accurate readings are an essential part of this process. Cuff fit size is an important part of determining BP correctly, so healthcare facilities should always have a wide range of cuffs in stock to suit all patients. BP monitoring device technology continues to advance, so while the basic principles will always remain the same, there is an increasing amount of choice available to assist healthcare providers in giving the best possible care while keeping costs down. Many facilities have found that standardization is an economical way to enable all healthcare workers to obtain precise measurements quickly and efficiently, potentially saving tens of thousands of dollars.

For many hospitals, disposable cuffs are an important resource in combating HAIs and allow them to demonstrate that they are doing everything possible to ensure that patients do not develop any further infections during their stay. Healthcare facilities face increasing pressure to do everything in their power to reduce the incidence of HAIs and disposable cuffs are an easy way to limit bacterial infection caused by reusable cuffs.

With such a wide range of BP cuff choices available, there should always be the right cuff available to suit every individual patient’s needs.

What type of BP cuff do you use in your facility? Have you considered standardizing? If you have standardized your BP cuffs, what difference has it made? We’d love to hear about your experiences in the comments.

Sources:

http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HighBloodPressure/AboutHighBloodPressure/Understanding-Blood-Pressure-Readings_UCM_301764_Article.jsp#.WJMUsIXXIdU

https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/index.htm

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230638387_Critical_care_The_eight_vital_signs_of_patient_monitoring

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1543468/

https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/news/press-releases/2015/landmark-nih-study-shows-intensive-blood-pressure-management-may-save-lives